Five heterodox groups of economists who should be brought out from under the shadow of the orthodox economists who have no answers for financial crises

Thursday, January 7, 2010 at 04:54PM

Thursday, January 7, 2010 at 04:54PM If you are as interested as I am in the fact that the most prestigious groups of economists were totally surprised by the recent financial meltdown, have no models or theory to explain it after the fact, and are continuing their virtual reality games as though nothing happened, you'll want to read this paper by Jamie Galbraith in the NEA Higher Education Journal. My summary:

While the two mainstream schools, Chicago (or freshwater or neoclassicists) vs. MIT (or saltwater or new Keynesians), have contended vigorously with each other over details, they remain united in a commitment to an all-encompassing theory expressed in mathematics. They are in the same "gentlemen's club" in which nobody loses face for predicting things that don't happen, failing to predict things that do happen, or maintaining positions that outsiders can clearly see are goofy. Galbraith describes five heterodox groups that did predict the recent crisis and similar crises in the past and says we would be better off if they had more resources and influence.

The hoariest are the "American Marxists" who believe the economic system is fundamentally flawed by conflicting power relationships and that its eventual collapse will be triggered by one of several events (they don't all agree on the specific type) like a collapse in the dollar, accumulating current account deficits, overextension of debt in the financial system, etc. Since these economists are "habitual Cassandras" and are uninterested in policy adjustments for what they think is a unsalvageable system, it's hard to see how they are helpful, but they did predict the financial crisis.

Dean Baker and others have predicted asset bubbles by observing large deviations from their means of relationships such as P/E ratios, home ownership prices to rents, etc. Critics complain that it relies on the assumption that the chosen relationship will revert to a mean not because there is a theoretical reason why it should but only because it always did in the past. The lack of theory is troubling to other economists, but these folks were right about the financial crisis and have a methodology that predicts reasonably well the sizes of adjustments.

Another group in Cambridge (UK) and the Levy Economics Institute studies relationships in the National Income and Product Accounts (which generate GDP) and argue, with some theoretical underpinnings, that large increases or decreases in Consumption, Private Investment, Government Spending, or Net Exports must induce opposite changes in certain other accounts and that at some point these shifts are unsustainable and must reverse. They too were right about the financial crisis.

Hyman Minsky and his followers like Barkley Rosser and Ping Chen developed a theory that stability in markets breeds instability and that self-generated boom-bust cycles are inevitable unless government intervenes to prevent hedging, which normally morphs into speculation (the obvious need to refinance in the future), from passing into the Ponzi phase (where ever-increasing amounts will have to be refinanced). This group warned against the policies of Alan Greenspan and Larry Summers that not only facilitated but actively encouraged what was obvious Ponzi financing, and they predicted the financial crisis.

The economics of John Kenneth Galbraith in The New Industrial State (1967) sought to focus less on markets and more on institutions (big corporations, labor unions, governments, etc.) and how those institutions function internally and in relation to each other. The mainstream economists hated and marginalized it. Jamie Galbraith followed this tradition in The Predator State (2008), arguing that after about 1970 there was a withering of internal controls in corporations, less governmental oversight, and other pressures that led to managements running amok, often blindly. As several financial crises (S&L, Dot.com, Enron/Worldcom, Sub-prime) were autopsied, a lack of control and irresponsible behavior is at the center of all. Other economists studying these institutional dynamics have pointed out recurrent patterns not only of irresponsibility and chaos but of fraud and looting and warned of recurrences if the institutions were not reformed. This group also predicted the financial crisis.

Finally, Galbraith argues that the "gentlemen's club" must be circumvented by university administrators, foundations, students, and others outside the mainstream economics departments to create academic space and public visibility for these versions of economics.

The closer we get to the real issues, the more interested I get in GCC legislation. Although showing promise, Stavins is still behind the curve in that regard.

There is probably no more important political fact than that carbon pricing is very bad for coal interests, nearly neutral for petroleum, and very good for natural gas. This results from starting by appeasing the god of economic efficiency with a system that generates a single price for all CO2 emissions regardless of source. That leads to the drama in Congress about trying to prevent the shuttering of the coal mining industry and write-off of coal-fired power plants (e.g., by making it possible to substitute “offsets” by “preserving” Amazon rain forests, etc.) and/or obscuring the attack on coal by assigning to the “market” responsibility for determining outcomes (so that elected representatives of the people can deny responsibility for lost livelihoods). A more realistic legislative approach might be to buy all the coal mines and turn them into wildlife preserves and soccer fields.

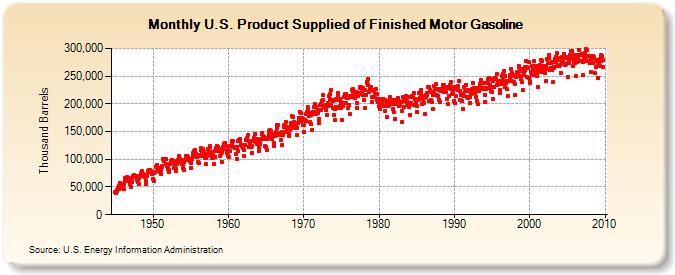

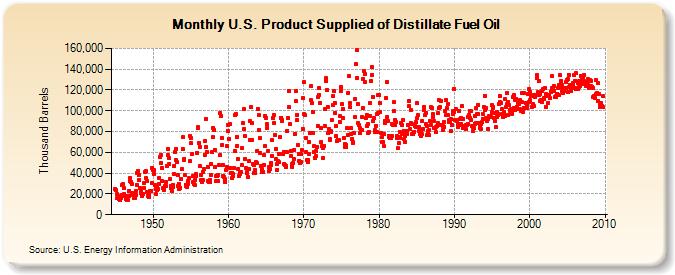

In support of the first sentence above, consider the following. According to CBO, a price of $191 per ton of CO2 would not reduce consumption of highway fuels at all below what they will be under existing CAFÉ standards. To see why this is so, consider how the $80/ton price recently proposed by Joseph Stiglitz would affect coal and gasoline. A ton of typical steam coal contains about 1400 lbs. of carbon, which will turn into 5,133 lbs. (2.57 tons) of CO2. If CO2 is assessed at $80 per ton, the price of a ton of coal would increase by $205. Since the national average coal price was $31.26 in 2008, that price increase would cause electricity generators to close their coal-fired plants as soon as possible and switch to natural gas, renewables, and (maybe) nuclear.

In contrast, $80 per ton for CO2 would raise the price of gasoline by only $0.80 per gallon (a gallon of gasoline generates ~20 lbs. or 1/100 of a ton of CO2). Obviously, that won't discourage use of highway fuels very much even though it would cost US consumers $110 billion per year in the aggregate. In the US, about 60% of petroleum is converted into gasoline; other major products are motor diesel, jet fuel, home heating oil, and a variety of industrial uses, none of which were addressed by the CBO report; however, I doubt a price increase of 20-30% in these fuels would dramatically reduce consumption of them either, but you use your own business judgment. Bottom line: a price of $80/ton of CO2 could cause an INCREASE in consumption of petroleum products as utilities switch from coal fired units to gas turbines (which were originally designed to burn petroleum distillates, not natural gas, in the stratosphere).

So why does the petroleum industry seem so upset by cap/trade? I suggest they are not really upset but are just routinely opposing and exploiting opportunity. They have a budget and team for federal government relations and will devote it to whatever issues on are on the table, which at the moment includes threatened government “interference” in their business—even if the “interference” might help their business. In contrast to this routine opposition, if you want to see what a petroleum industry full court press looks like, if you want to see the sky over DC darkened by corporate jets and the finance chairs of Senate re-election campaigns worked to exhaustion booking contributions, bring a repeal of the IRC oil depletion allowance close to a floor vote. Furthermore, it is routine in Washington to demand something of value in exchange for any legislative initiative that can be plausibly claimed to have an adverse effect on one's industry. This isn’t a crisis for the oil industry—it’s an opportunity.

From EPA’s most recent report on US contributions to global climate change, using 2006 data: CO2 accounts for 85% of total greenhouse gas emissions, 94% of which come from burning fossil fuels, and about 41% of that comes from coal. If petroleum consumption will not change substantially and natural gas consumption will increase, any aggregate net change must come from reducing coal consumption. Legislation that does not respond head-on to this reality may pave the way to re-election of incumbents but won’t ameliorate the GCC problem.