What if we stopped reporting GDP?

Sunday, May 16, 2010 at 03:30PM

Sunday, May 16, 2010 at 03:30PM In January 2009, I posted to say Gross Domestic Product numbers do not provide an accurate picture of our nation's economic health and to call on the Obama Administration to adopt other metrics that would measure progress toward its economic goals. Later I learned that an international commission appointed by French President Sarkozy and headed by Joseph Stiglitz had been working on something like this since the spring of 2008. A primary driver of this effort was the widespread belief that GDP is an inadequate and often misleading measure of economic and social wellbeing and progress, as Stiglitz wrote here just before the report was issued September 14, 2009:

The big question concerns whether GDP provides a good measure of living standards. In many cases, GDP statistics seem to suggest that the economy is doing far better than most citizens' own perceptions. Moreover, the focus on GDP creates conflicts: political leaders are told to maximize it, but citizens also demand that attention be paid to enhancing security, reducing pollution, and so forth - all of which might lower GDP growth. GDP is misleading in many ways.

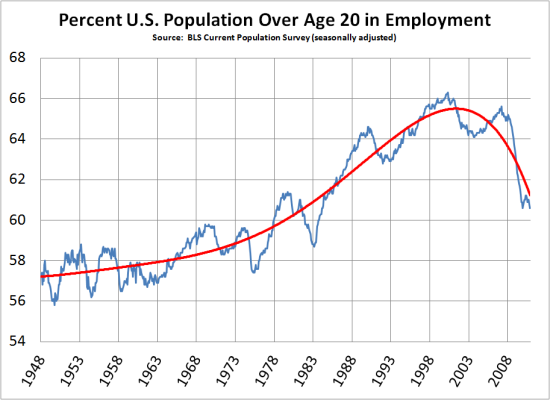

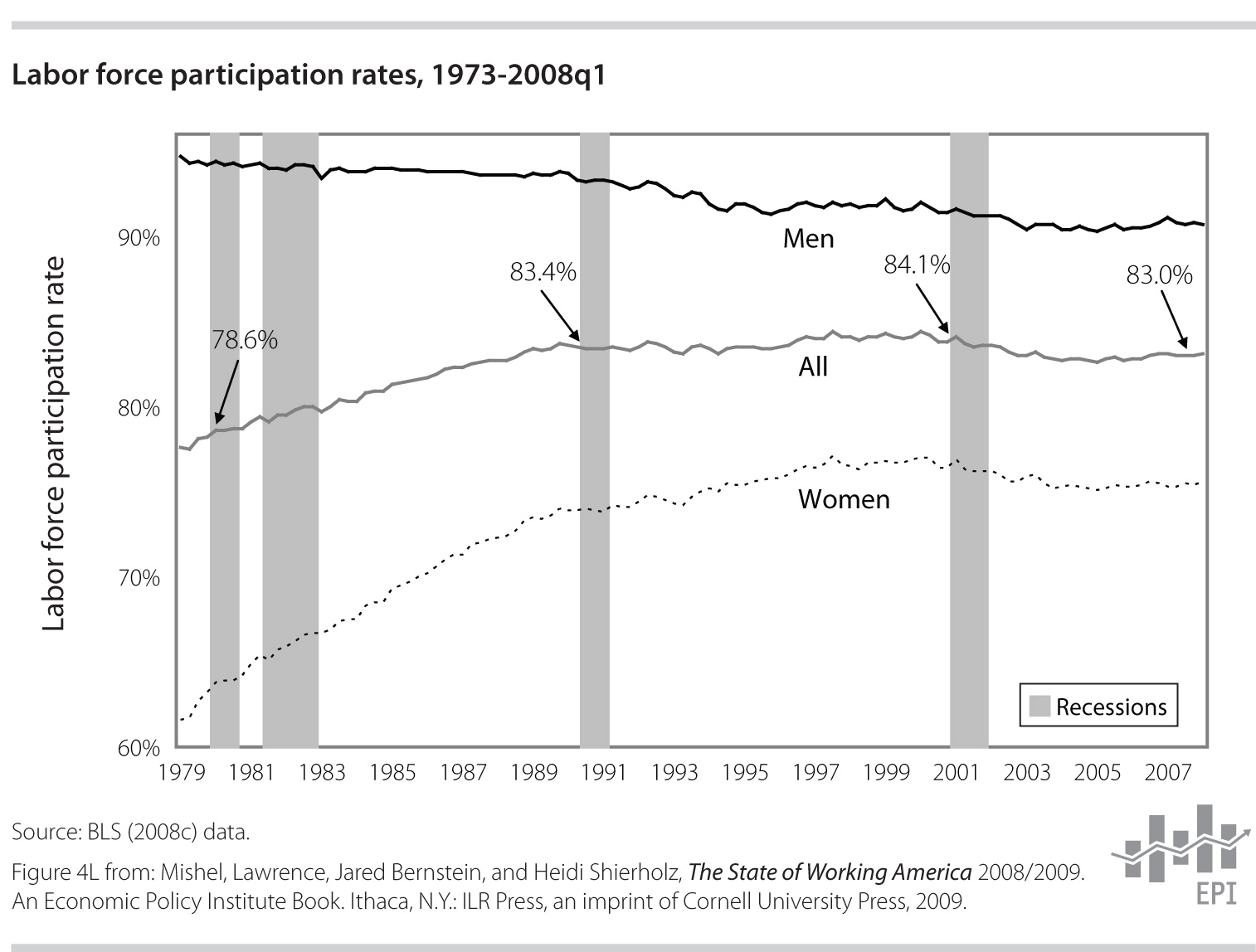

For example, GDP is no longer a reasonable proxy for middle-class incomes or unemployment rates. Median incomes got decoupled from GDP as long ago as 1973, and in the 21st Century real median incomes actually went down while GDP was rising. Our labor force participation rate has been declining since 2000, as has non-residential investment, and our current account deficit has been a tribute paid to foreigners of up to 6% since 1983. When recovering from the previous two recessions and this one, the unemployment rate has come down so slowly that they were referred to as "jobless recoveries." The traditional worry in a period of GDP growth has been inflation, but inflation hasn't been a problem in the US since 1984. No doubt the Fed looks at the rate of change in GDP to help it make short-term interest rate decisions, but the Fed looks at many other data sets too. So here's my proposal: Get other more appropriate metrics in place with a decent history (with the past reconstructed if possible), and then de-emphasize and eventually eliminate reports of GDP. One way to de-emphasize would be to change the frequency of reporting from quarterly to annually.

The best reporting I have seen about the work of the "Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress" is in this NYT Magazine piece. The Commission has recommended that people need a "dashboard" of metrics, just as they do when driving a car. (Only one gauge showing only speed would not be enough, but having dozens of gauges would be too confusing.) A new non-profit, State of the USA, funded inter alia by Hewlett, MacArthur, and Rockefeller foundations, is developing a website intended to serve as a kind of dashboard. As a sample, it has an interactive graphic comparing the US against other nations for healthcare costs versus life expectancy at birth from 1960 to 2007—pretty dramatic, and not in a good way if you're an American.

Skeptic

Skeptic

I first suggested we "Forget about GDP and Start Tracking Family Incomes" in this December 2007 post.

Skeptic

Skeptic

I tuned up the argument against relying on GDP in the following comment first posted on this string in Mark Thoma's blog.

The immediate post-WWII period Krugman highlighted [here and here] to show what was possible in America was a time when rising tides lifted all boats--yachts and dinghies equally. Real hourly earnings of production workers increased in lock-step with GDP per production worker, and so did real median family incomes. In those days, if you knew what GDP was doing, you knew a great deal about how ordinary Americans were doing economically. However, that is no longer true and hasn't been for several decades. Consequently, GDP-based arguments about the general welfare and how the real economy will function in the future are no longer valid. In 1962, real GDP per production worker started increasing faster than real hourly earnings, which stopped growing altogether in 1973 and have been stagnant ever since except for a 5-year surge in the late 1990s. Similarly, real median family income fell away from real per-capita GDP in 1978 and has continued to diverge widely. You can see these and other graphs, links, and a discussion here. http://www.realitybase.org/journal/2009/3/10/the-american-dream-died-in-february-1973.html The explanation is obvious when you look at productivity and compensation. From 1973 to 2007 labor productivity increased about 85%, but median compensation increased only about 15%. http://www.stateofworkingamerica.org/tabfig/2008/03/SWA08_Chapter3_Wages_r2_Fig-3O.jpg The Treaty of Detroit was abrogated--almost all productivity gains were captured by the owners, managers, and servants of capital. GDP growth has also gotten decoupled from the unemployment rate and from labor market participation rates, with the result that for the last two decades all three recessions have ended in "jobless recoveries." As far as I can tell, the only reason to keep reporting GDP is to accommodate all the folks running macroeconomic models that generate GDP outputs and not much else that is useful.

Skeptic

Skeptic

It’s not just that GDP is not correlated with median income and other indicia of welfare, we can’t predict GDP anyway. Nick Rowe points out here that typical macroeconomic models compute present GDP output from a variety of present inputs such as government spending and employment, but that the models don’t compute future GDP from current inputs. To get future GDP outputs, the modelers typically guess at the future inputs—which is no more reliable than just guessing at future GDP. Garbage in, garbage out.

In contrast, a “weather prediction model” looks though a database to find all the past occasions that had the same combination of parameters (temperature, barometric pressure, etc.) as today and then looks to see what actually happened the next day on each of those prior occasions. If on 83% of those prior occasions it rained the next day, the forecaster will predict an 83% probability of rain tomorrow. Apparently, macroeconomists don’t use that approach at all, presumably because the number of important parameters is too large and the database of prior events is too small.

There are many thoughtful comments on the Rowe post by apparently well-informed people. I would add that maybe the method Rowe criticizes is not 100% GIGO because if the modeler guesses at all the inputs he can avoid making a GDP prediction that could only happen if one or more of the inputs were implausible.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Another use for which GDP is of questionable utility is in the sovereign debt to GDP ratio, which has been traditionally used to assess whether a national government has taken on more debt than is safe and must adopt an austerity program. In that context GDP is used to indicate whether the government has enough practical taxing power to assure markets that the debt is risk free--not only in terms of potential default but the risk that the government may be tempted to inflate away the debt. However, the tax base has been dramatically changed since Reagan took office in 1981--away from high earners, accumulated wealth, corporate income taxes, and other taxes on wealth and toward earned income and especially on the earned income of those who are not super-rich. Since taxation now bears relatively more heavily on the incomes of those whose incomes are stagnating and less on the dynamic and wealthy parts of the economy, the practical taxing power is a smaller fraction of GDP than it used to be. Therefore, a 1:1 ratio of debt to GDP (or any other ratio) should give less comfort to bond holders today than it did three decades ago. Unfortunately, there doesn't seem to be another obviously more appropriate metric than GDP to assess practical taxing power--unless it is to compare with tax rates in the past.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Research has shown in the last four years that GDP measurement methods miss some effects of offshoring manufacturing and service jobs and causes overstatement of US GDP. This probably helps explain the "jobless recoveries" we've had in the last two decades. Louis Uchitelle reported here on a gathering of government and academic economists last November to try to fix the problem.

WASHINGTON — A widening gap between data and reality is distorting the government’s picture of the country’s economic health, overstating growth and productivity in ways that could affect the political debate on issues like trade, wages and job creation.

The shortcomings of the data-gathering system came through loud and clear here Friday and Saturday at a first-of-its-kind gathering of economists from academia and government determined to come up with a more accurate statistical picture.

The fundamental shortcoming is in the way imports are accounted for. A carburetor bought for $50 in China as a component of an American-made car, for example, more often than not shows up in the statistics as if it were the American-made version valued at, say, $100. The failure to distinguish adequately between what is made in America and what is made abroad falsely inflates the gross domestic product, which sums up all value added within the country.

American workers lose their jobs when carburetors they once made are imported instead. The federal data notices the decline in employment but fails to revalue the carburetors or even pinpoint that they are foreign-made. Because it seems as if $100 carburetors are being produced but fewer workers are needed to do so, productivity falsely rises — in the national statistics.

“We don’t have the data collection structure to capture what is happening in a real time way, or what is being traded and how it is affecting workers,” said Susan Houseman, a senior economist at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research in Kalamazoo, Mich., who has done pioneering research in the field. “We have no idea how to measure the occupations being offshored or what is being inshored.”

The statistical distortions can be significant. At worst, the gross domestic product would have risen at only a 3.3 percent annual rate in the third quarter instead of the 3.5 percent actually reported, according to some experts at the conference. The same gap applies to productivity. And the spread is growing as imports do.

That may help to explain why the recovery from the 2001 recession was a jobless one for many months and why the recovery from this recession is likely to generate few jobs for many months.

. . . .

The federal agencies that compile the nation’s statistics increasingly acknowledge that they lack the detailed data needed to calculate the impact of imported goods and services as imports rise from an insignificant 5 percent of all economic activity 35 years ago to more than 12 percent today, not counting petroleum. As a result, many imports are valued as if they were made in the United States and therefore higher in price than their imported counterparts.

The problem is particularly acute in manufacturing. Imported components constitute an ever greater share of the computers, autos, appliances and other finished merchandise that roll off assembly lines in the United States — and an ever greater share of all of the nation’s imports.

. . . .

The same holds for services. An accounting firm in New York with 50 employees outsources some of its functions to less expensive accountants in India: the paperwork on an income tax return, for example. That work comes back to New York by computer transmission and is billed at New York rates, as if it were value added in this country.

Grappling with these blind spots, nearly all of the 80 experts at the conference, which was sponsored by the Upjohn Institute and the National Academy of Public Administration, agreed that the statistics now published tend to overstate the strength of the economy. That view was shared by those who attended from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Federal Reserve, all big players in measuring economic performance.

BusinessWeek had a longer story here in 2007 as the Houseman work was just becoming public. Some excerpts suggesting the effect may be quite large:

By BusinessWeek's admittedly rough estimate, offshoring may have created about $66 billion in phantom GDP gains since 2003 (page 31). That would lower real GDP today by about half of 1%, which is substantial but not huge. But put another way, $66 billion would wipe out as much as 40% of the gains in manufacturing output over the same period.

It's important to emphasize the tenuousness of this calculation. In particular, it required BusinessWeek to make assumptions about the size of the cost savings from offshoring, information the government doesn't even collect.. . . .

Pat Byrne, the global managing partner of Accenture Ltd.'s (ACN ) supply-chain management practice, goes even further, suggesting that "at least half of U.S. productivity [growth] has been because of globalization." But quantifying this is tough, he notes, because most companies don't look at how much of their productivity growth is onshore and how much is offshore. "I don't know of any companies or industries that have tried to measure this. Maybe they don't even want to know."

Phantom GDP helps explain why U.S. workers aren't benefiting more as their companies grow ever more efficient. The cost savings that companies are reaping "don't represent increased productivity of American workers producing goods and services in the U.S.," says Houseman. In contrast, compensation of senior executives is typically tied to profits, which have soared alongside offshoring.

ADDED 6/24/2011: Houseman and a colleague summarize their research in an accessible fashion in this McKinsey Global Institute report.

Skeptic

Skeptic

Matt Iglesias reports thatSveriges Riksbank deputy governor Lars E.O. Svensson has argued for focusing directly on unemployment as the best measure of the output gap.