One way to understand the feud among macroeconomists is that some of them are "engineers" focused on solving real world economic problems and some are "scientists" focused on improving mathematical models of their theories, according to Harvard professor Greg Mankiw in this very interesting paper from 2006. [Please see 6/26/2020 update for a working link.] Mankiw says the "engineers" trace their roots to MIT (Samuelson and Solow), while the "scientific" tradition is rooted in the University of Chicago (Friedman, Barro, and Lucas). (This is often referred to as the "saltwater-freshwater" schism.) He notes that many prominent economic engineers have taken senior positions in government under both Democratic and Republican administrations, as he did in George W. Bush's first term as chair of CEA, but that he cannot think of a single prominent economic scientist who has done that.

After a fascinating summary of the main research threads and theories since the 1930s, he surprised me by concluding that almost none of the developments in economic science since WWII has affected how the economist-engineers in Washington do their jobs.

The real world of macroeconomic policymaking can be disheartening for those of us who have spent most of our careers in academia. The sad truth is that the macroeconomic research of the past three decades has had only minor impact on the practical analysis of monetary or fiscal policy. The explanation is not that economists in the policy arena are ignorant of recent developments. Quite the contrary: The staff of the Federal Reserve includes some of the best young Ph.D.'s, and the Council of Economic Advisers under both Democratic and Republican administrations draws talent from the nation's top research universities. The fact that modern macroeconomic research is not widely used in practical policymaking is prima facie evidence that it is of little use for this purpose. The research may have been successful as a matter of science, but it has not contributed significantly to macroeconomic engineering.

Nor has there been a great effect on college textbooks, which still bear strong resemblance to Samuelson's 1948 Economics, according to Mankiw who is author of today's most widely used introductory college economics textbook. The most prominent alternative textbook, introduced by Chicago's Robert Barro in 1984, failed to catch on.

Although Mankiw doesn't discuss it, many of the ideas that have not been implemented by the engineers and have been largely abandoned by the scientists nevertheless had, and continue to have, great political influence. For that reason, I summarize below Mankiw's history of the evolution of mainstream economic thought since the Great Depression. Among the theories and concepts that flash across the screen are the neoclassical-Keynesian synthesis, an economy stuck in a suboptimal equilibrium, sticky prices, animal spirits, fiscal stimulus, Phillips curve, monetarism, rational expectations, real business cycle theory, short run and long run behavior, imperfect competition, dynamic stochastic general equilibrium theory, and the new neoclassical synthesis. Clearly, this is my wonkiest post ever.

Although the word "macroeconomics" first appears in the scholarly literature in the 1940s, economists had been paying attention for at least 200 years to the main concerns of macroeconomics—inflation, unemployment, economic growth, the business cycle, monetary policy, and fiscal policy. The Great Depression brought the realization that economists did not understand why there was no spontaneous recovery until John Maynard Keynes explained in General Theory (1936) that markets can get stuck in an unfavorable equilibrium because of a general pessimism and lack of confidence or animal spirits and because prices, especially labor prices, tend to be sticky. When an economy was stuck in a depression, Keynes prescribed massive government spending with borrowed money (fiscal stimulus) to generate personal incomes that would boost aggregate demand which would stimulate hiring and investment, turning stagnation into a resumption of growth.

Many who had the life-changing experience of living through the Great Depression and later became prominent economists seized on these ideas and became leaders of the "Keynesian Revolution." They undertook to turn Keynes' grand vision into a simpler, more concrete and precise model.

One of the first and most influential attempts was the IS-LM [Investment/Saving-Liquidity preference/Money supply] model proposed by the 33-year-old John Hicks (1937). The 26-year-old Franco Modigliani (1944) then extended and explained the model more fully. To this day, the IS-LM model remains the interpretation of Keynes offered in the most widely used intermediate-level macroeconomics textbooks. . . .

[Meanwhile] . . ., econometricians such as Klein were working on more applied models that could be brought to the data and used for policy analysis. Over time, in the hope of becoming more realistic, the models became larger and eventually included hundreds of variables and equations. By the 1960s, there were many competing models, each based on the input of prominent Keynesians of the day, such as the Wharton Model associated with Klein, the DRI (Data Resource, Inc.) model associated with Otto Eckstein, and the MPS (MIT-Penn-Social Science Research Council) model associated with Albert Ando and Modigliani. These models were widely used for forecasting and policy analysis. The MPS model was maintained by the Federal Reserve for many years and would become the precursor to the FRB/US model, which is still maintained and used by Fed staff.

Although these models differed in detail, their similarities were more striking than their differences. They all had an essentially Keynesian structure. In the back of each model builder's mind was the same simple model taught to undergraduates today: an IS curve relating financial conditions and fiscal policy to the components of GDP, an LM curve that determined interest rates as the price that equilibrates the supply and demand for money, and some kind of Phillips curve that describes how the price level responds over time to changes in the economy."

. . . .

Yet the Keynesian revolution cannot be understood merely as a scientific advance. To a large extent, Keynes and the Keynesian model builders had the perspective of engineers. They were motivated by problems in the real world, and once they developed their theories, they were eager to put them into practice. Until his death in 1946, Keynes himself was heavily involved in offering policy advice. So, too, were the early American Keynesians. Tobin, Solow, and Eckstein all took time away from their academic pursuits during the 1960s to work at the Council of Economic Advisers. The Kennedy tax cut, eventually passed in 1964, was in many ways the direct result of the emerging Keynesian consensus and the models that embodied it.

The Phillips curve, based on a 1958 paper, was incorporated into the Keynesian model in the 1960s. It purported to describe a fixed relationship between the unemployment rate and the inflation rate—if one was high the other would be low and vice versa, supposedly making it possible for policymakers to choose among various combinations of unemployment and inflation. It underpins the Congressional mandate to the Fed that it must consider both inflation and unemployment in policy making, unlike some other central banks that are mandated only to limit inflation. Although modified versions of a Phillips curve are still used in econometric models today, the 1970s versions could not explain the coincidence of high inflation and high unemployment ("stagflation") of that decade [See 4/16/11 Update], and that opened the door (at ix) to rival theories being developed and taught in Chicago.

In their article After Keynesian Macroeconomics, Sargent and Lucas (1979) wrote, "For policy, the central fact is that Keynesian policy recommendations have no sounder basis, in a scientific sense, than recommendations of non-Keynesian economists or, for that matter, noneconomists." Although Sargent and Lucas thought Keynesian engineering was based on flawed science, they knew that the new classical school (circa 1979) did not yet have a model that was ready to bring to Washington: "We consider the best currently existing equilibrium models as prototypes of better, future models which will, we hope, prove of practical use in the formulation of policy." They also ventured that such models would be available "in ten years if we get lucky.

Although Sargent and Lucas admitted their models were not ready for Washington (and were then indeed as scientifically flawed as the Keynesian models) some of the ideas behind the Chicago models were nevertheless kidnapped from the cradle and taken to Washington where they quickly became and remain hugely influential on policy decisions and public discourse about economics. In large part this was because their escalating attacks on the Phillips curve at a time when it pretty clearly wasn't working discredited the whole Keynesian model, including its valid ideas about the possibilities for stagnation, sticky prices, and fiscal stimulus of aggregate demand. The Chicago ideas were also successful because they supported existing political preferences for reduced government spending and laissez faire markets and because Milton Friedman was a weekly Newsweek columnist from 1966 to 1984, an advisor to Ronald Reagan, the host of a TV series about political economy, and generally a prominent public intellectual. During this period, Chicago launched three big macroeconomic ideas emphasizing the virtues of markets and the failings of government.

The first wave of new classical economics was monetarism, and its most notable proponent was Milton Friedman. Friedman's (1957) early work on the permanent income hypothesis was not directly about money or the business cycle, but it certainly had implications for business cycle theory. It was in part an attack on the Keynesian consumption function, which provided the foundation for the fiscal policy multipliers that were central to Keynesian theory and policy prescriptions. If the marginal propensity to consume out of transitory income is small, as Friedman's theory suggested, then fiscal policy would have a much smaller impact on equilibrium income than many Keynesians believed.

Friedman and Schwartz's (1963) Monetary History of the United States was more directly concerned with the business cycle and it, too, undermined the Keynesian consensus. Most Keynesians viewed the economy as inherently volatile, constantly buffeted by the shifting "animal spirits" of investors. Friedman and Schwartz suggested that economic instability should be traced not to private actors but rather to inept monetary policy.

Although the Keynesian models dealt with the money supply among other factors, the monetarists said "only money matters." In its turn, strict monetarism was quickly displaced in academia by "rational expectations" theory, also developed in Chicago.

In a series of highly influential papers, Robert Lucas extended Friedman's argument. In his Econometric Policy Evaluation: A Critique, Lucas (1976) argued that the mainstream Keynesian models were useless for policy analysis because they failed to take expectations seriously; as a result, the estimated empirical relationships that made up these models would break down if an alternative policy were implemented. Lucas (1973) also proposed a business cycle theory based on the assumptions of imperfect information, rational expectations, and market clearing. In this theory, monetary policy matters only to the extent to which it surprises people and confuses them about relative prices. Barro (1977) offered evidence that this model was consistent with U.S. time-series data. Sargent and Wallace (1975) pointed out a key policy implication: Because it is impossible to surprise rational people systematically, systematic monetary policy aimed at stabilizing the economy is doomed to failure.

The third wave of new classical economics was the real business cycle theories of Kydland and Prescott (1982) and Long and Plosser (1983). Like the theories of Friedman and Lucas, these were built on the assumption that prices adjust instantly to clear markets—a radical difference from Keynesian theorizing. But unlike the new classical predecessors, the real business cycle theories omitted any role of monetary policy, unanticipated or otherwise, in explaining economic fluctuations. The emphasis switched to the role of random shocks to technology and the intertemporal substitution in consumption and leisure that these shocks induced.

As a result of the three waves of new classical economics, the field of macroeconomics became increasingly rigorous and increasingly tied to the tools of microeconomics. . . .

This commitment to rigorous mathematical scientific modeling and to microeconomic foundations had become the hallmark of new classical economics. The methodology was more important than the particular postulates modeled.

Today, many macroeconomists coming from the new classical tradition are happy to concede to the Keynesian assumption of sticky prices as long as this assumption is imbedded in a suitably rigorous model in which economic actors are rational and forward-looking. Because of this change in emphasis, the terminology has evolved, and this class of work now often goes by the label "dynamic stochastic general equilibrium" theory.

Meanwhile, the Keynesians had not gone away or been converted. They too had been troubled by the absence of micro-foundations for their macroeconomics. While the freshwater economists had rejected Keynes outright and set about building their own theories and models, the saltwater economists tried to improve the neoclassical-Keynesian synthesis by incorporating micro-foundations.

All modern economists are, to some degree, classical. We all teach our students about optimization, equilibrium, and market efficiency. How to reconcile these two visions of the economy—one founded on Adam Smith's invisible hand and Alfred Marshall's supply and demand curves, the other founded on Keynes's analysis of an economy suffering from insufficient aggregate demand—has been a profound, nagging question since macroeconomics began as a separate field of study.

Early Keynesians, such as Samuelson, Modigliani, and Tobin, thought they had reconciled these visions in what is sometimes called the "neoclassical-Keynesian synthesis." These economists believed that the classical theory of Smith and Marshall was right in the long run, but the invisible hand could become paralyzed in the short run described by Keynes. The time horizon mattered because some prices—most notably the price of labor—adjusted sluggishly over time. Early Keynesians believed that classical models described the equilibrium toward which the economy gradually evolved, but that Keynesian models offered the better description of the economy at any moment in time when prices were reasonably taken as predetermined.

Mankiw describes (at 10-12) specific problems that were worked out between about 1971 and about 1990 and concludes—

In my judgment, these three waves of new Keynesian research added up to a coherent microeconomic theory for the failure of the invisible hand to work for short-run macroeconomic phenomena. We understand how markets interact when there are price rigidities, the role that expectations can play, and the incentives that price setters face as they choose whether or not to change prices. As a matter of science, there was much success in this research (although, as a participant, I cannot claim to be entirely objective). The work was not revolutionary, but it was not trying to be. Instead, it was counterrevolutionary: Its aim was to defend the essence of the neoclassical-Keynesian synthesis from the new classical assault.

In the late 1990s a new synthesis between the freshwater and saltwater approaches emerged, although it may have been only an uneasy truce (which broke down in the wake of the global financial crisis).

Like the neoclassical-Keynesian synthesis of an earlier generation, the new synthesis attempts to merge the strengths of the competing approaches that preceded it. From the new classical models, it takes the tools of dynamic stochastic general equilibrium theory. Preferences, constraints, and optimization are the starting point, and the analysis builds up from these microeconomic foundations. From the new Keynesian models, it takes nominal rigidities and uses them to explain why monetary policy has real effects in the short run. The most common approach is to assume monopolistically competitive firms that change prices only intermittently, resulting in price dynamics sometimes called the new Keynesian Phillips curve. The heart of the synthesis is the view that the economy is a dynamic general equilibrium system that deviates from a Pareto optimum because of sticky prices (and perhaps a variety of other market imperfections).

. . . .

With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that the new classical economists promised more than they could deliver. Their stated aim was to discard Keynesian theorizing and replace it with market-clearing models that could be convincingly brought to the data and then used for policy analysis. By that standard, the movement failed. Instead, they helped to develop analytic tools that are now being used to develop another generation of models that assume sticky prices and that, in many ways, resemble the models that the new classicals were campaigning against.

The new Keynesians can claim a degree of vindication here. The new synthesis discards the market-clearing assumption that Solow called "foolishly restrictive" and that the new Keynesian research on sticky prices aimed to undermine. Yet the new Keynesians can be criticized for having taken the new classicals' bait and, as a result, pursuing a research program that turned out to be too abstract and insufficiently practical. Paul Krugman (2000) offers this evaluation of the new Keynesian research program: "One can now explain how price stickiness could happen. But useful predictions about when it happens and when it does not, or models that build from menu costs to a realistic Phillips curve, just don't seem to be forthcoming." Even as a proponent of this line of work, I have to admit that there is some truth to that assessment.

This post would not be complete without mentioning that the "mainstream economics" described by Mankiw above omits many important economics ideas and ongoing work. For example, the work of Hyman Minsky and his followers on asset price bubbles and crashes has gained recent prominence as people try to understand why the mainstream economists were blindsided by the global financial crisis (which hadn't happened yet when Mankiw wrote this paper). Whereas the mainstreamers had accepted the Keynesian lesson that prices could be sticky and had mathematical models to study the resulting effects, they were not considering—and their models did not accommodate—the opposite problem that asset prices can be very volatile. Now, 18 months after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, we still don't seem to have a mainstream answer about how to model and make policy decisions about asset price volatility or what textbooks should say about this.

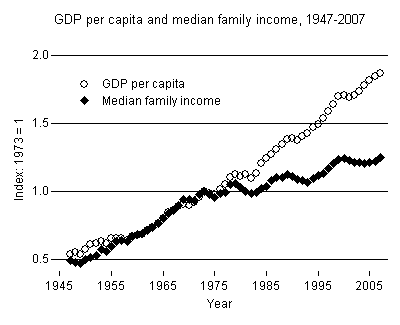

Another area of economics that is floundering is understanding what policy changes could stimulate growth and prosperity in undeveloped countries. Mankiw explains that the "Great Moderation" of the 1990s caused mainstream economists to think business cycles were a problem of the past and not worth studying, and they turned their attention to growth models, which inspired (in my words, not Mankiw's) other half-baked policies like the Washington Consensus about development, which is already being abandoned by the economist-engineers. There were other reasons for this diversion of attention, including this one:

There is also a fourth, more troublesome reason why budding macroeconomists of the 1990s were drawn to study long-run growth rather than short-run fluctuations: the tension between new classical and new Keynesian worldviews. While Lucas, the leading new classical economist, was proclaiming that "people don't take Keynesian theorizing seriously anymore," leading Keynesians were equally patronizing to their new classical colleagues. In his AEA Presidential Address, Solow (1980) called it "foolishly restrictive" for the new classical economists to rule out by assumption the existence of wage and price rigidities and the possibility that markets do not clear. He said, "I remember reading once that it is still not understood how the giraffe manages to pump an adequate blood supply all the way up to its head; but it is hard to imagine that anyone would therefore conclude that giraffes do not have long necks.

Update on Saturday, March 13, 2010 at 09:08PM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

Peter Radford, writing Whither Economics? What do we tell the students? in Real-World Economics Review, has this to say about Mankiw's dichotomy:

I prefer a slightly different division to Mankiw’s. There are economists who study economies, and there are economists who study economics. Both theorize. Both search for regularities. Both offer what they think is practical advice. Both develop technologies based upon their theories. There are engineers and scientists in both camps. The difference is more fundamental than Manikiw suggests.

Those who study economies are naturally drawn to real world economics, whether they think of themselves in that camp or not, because of their attention to the world around them. If the real world and its variety, its institutions, cultures, religions, its diversity and even its geography influence a theorist’s starting point then they are studying economies in a real world sense.

Those who prefer to investigate the properties of equilibrium, rational expectations, and efficient markets are studying economics. They are dealing with abstraction since their starting point is an artefact created from assumptions, axioms and the like. Their hope is that they can elicit useful statements transferable to the real world, but yet not study the real world.

The problem with this split is that it implies that economics over the years has come to represent something other than the study of economies, and this is the source of the conflict that now rages. The realists complain about the irrelevancy of orthodoxy now that it has become little more than a self-referential series of models whose major value resides in their elegance and sparseness. Theirs is a feeling that economics should engage the real world rather than resist it. It is a feeling that a true ‘science’ should not view so much of reality as a failure to conform with theory. Rather it should explain the texture of reality, albeit through the prism of mathematics and models.

Update on Monday, April 26, 2010 at 03:26PM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

Paul Krugman explains here the time and the issue that created the freshwater-saltwater schism. Robert Lucas and Robert Barro (Chicago) advanced the "rational expections" model and when it became clear that it didn't work they went on to "real business cycle" theory while the saltwater folks became "New Keynesians."

Update on Tuesday, June 29, 2010 at 08:52AM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

Paul Krugman links to some current criticisms of modern freshwater macro and gives his summary of what went wrong here.

Update on Saturday, October 9, 2010 at 01:48PM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

More in the same vein and a complaint by saltwater economists about how hard it became to get published unless they disguised their models to look like fresh water "modern macroeconomics."

Update on Friday, November 26, 2010 at 12:36PM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

Paul Krugman's narration here is less granular but similar, as he considers whether forgetting the economic policy lessons of the Great Depression was perhaps inevitable because of an instability of intellection moderation.

Update on Monday, November 29, 2010 at 08:36AM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

Peter Radford points out that all the major strains of modern economics have failed to resolve the internal contradictions between their respective micro and macro theories.

Update on Saturday, March 19, 2011 at 04:48PM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

Update on Saturday, April 9, 2011 at 10:38AM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

Larry Summers, until recently chief economic policy advisor to President Obama, said in a recent interview by Martin Wolf that in addressing the debt crisis and Great Recession, they considered the basic Keynesian IS-LM model supplemented by liquidity trap considerations and paid no attention to DSGE models and micro foundations papers. Mark Thoma, who was present, reports it here and quotes a bit from The Economist's writeup and links to it.

His broader point—reinforced by his mentions of the knowledge contained in the writings of Bagehot, Minsky, Kindleberger, and Eichengreen—was, I think, that while it would be wrong to say economics or economists had nothing useful to say about the crisis, much of what was the most useful was not necessarily the most recent, or even the most mainstream. Economists knew a great deal, he said, but they had also forgotten a great deal and been distracted by a lot.

Update on Saturday, April 16, 2011 at 09:58AM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

A series of graphs plotting inflation rates vs. unemployment rates from 1948 to 2007 is presented by Catherine Mulbrandon at VisualizingEconomics. Her interpretation is that the Phillips relationship held only in the 1960s.

Update on Monday, July 18, 2011 at 03:02PM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

Peter Radford identifies the 1930s as a time of great political ferment that created schisms in economic doctrines rather than the other way around. The doctrines of that time are all incomplete, very much alive, and serve different political interests. An excerpt:

The divisions that carve economics apart are extraordinarily deep. But very often they are political in their origins. They creep into economics only after having been formed in politics. Economics is hopelessly ideological.

Thus the Austrian school agrees with the neoclassical camp that government intervention in an economy is almost always a negative effect. The Keynesians adamantly disagree.

But the Austrians also embrace uncertainty. That splits them part from the neoclassicists who build their theories on presumptions of varying degrees of certainty. The Keynesians have uncertainty at the core of their ideas, so they agree on this with the Austrians.

Money disappears from neoclassicism which is, essentially, a theory of barter, while Keynes brings money into the center. But he, rather curiously, ignores banks.

The Austrians, via Hayek, have a great deal to say about the centrality of knowledge and its evolution which makes them close to evolutionary economics and more comfortable with behavioral economics, yet they have a naive view of production and entrepreneurial activity which means they fall short of embracing complexity and thus have nothing much to say about the modern firm.

Which is odd, since institutions play a greater role in Austrian theory than in either Keynes or neoclassicism. This leaves new institutional economics straddling the gap between neoclassicism and the Austrian school.

Update on Friday, April 6, 2012 at 02:44PM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

Update on Saturday, April 7, 2012 at 10:29AM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

Unlearning Economics lays out the implicit assumptions he thinks all neoclassical economists (freshwater and saltwater) make and then never discuss.

(1) Methodological individualism – the economy is modeled on the basis of the behaviour of individual agents.

(2) Methodological instrumentalism – individuals act in accordance with certain preferences rankings, to attain some end goal that they deem desirable.

(3) Methodological equilibration – given the above two, macroeconomics asks what will happen if we assume equilibrium. Note that this doesn’t necessarily posit that the system will end up in equilibrium (although that is often the case), but rather seeks to find out what will happen if we use equilibrium as an epistemological starting point.

This foundation makes it hard for them to credit the work of other schools whose work starts with different assumptions. Unlearning sees this talking-past-each-other problem in the current argument between Keen and Krugman.

Update on Friday, June 26, 2020 at 02:50PM by

Skeptic

Skeptic

The link to Mankiw's paper has rotted away. The official citation is Mankiw, N. G., The Macroeconomist as Scientist and Engineer. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006; 20 (4) :29-46. The link to a PDF is working today.

Wednesday, March 31, 2010 at 09:12AM

Wednesday, March 31, 2010 at 09:12AM

Skeptic

Skeptic