Marshall Auerback: Chinese Trade Policy Must Focus on Social Consequences

Thursday, January 13, 2011 at 02:47PM

Thursday, January 13, 2011 at 02:47PM Republished with permission from New Deal 2.0:

Focusing on currency isn’t going to cut it for America’s workers.

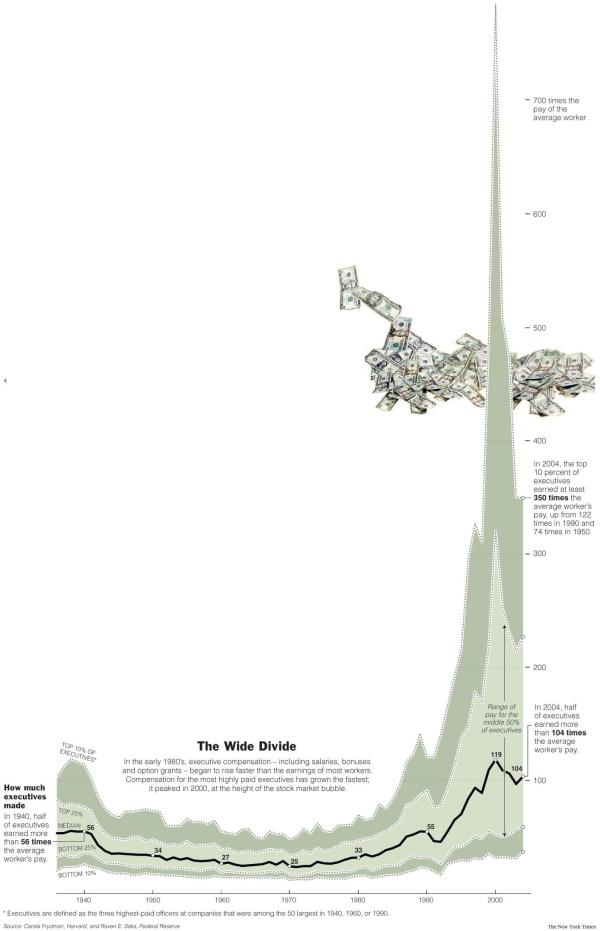

You have to have a sense of irony to watch the latest maneuvers on trade with China. Obama continues to turn his administration into “Clinton Mark III”. (Enter Gene Sperling and Jacob Lew, following the revolving door departures of Peter Orszag and Larry Summers). The president continues to turn to many of the very folks who paved the way for China’s eclipse of the US economy. Granting China normal trade status under the World Trade Organization, as President Clinton did during his presidency, facilitated the expansion of China’s external sector, which coincided with a big step-up in the ratio of fixed capital formation to GDP. The WTO entry is how China managed to increase its growth rate from 2002 to 2007, using an undervalued currency to cannibalize the tradeables sector of its main Asian competitors and increasingly hollowing out US manufacturing in the process. At this stage, however, despite the ongoing requests by Treasury Secretary Geithner that “China needs to do more” on its currency, a simple revaluation of the yuan won’t cut it.

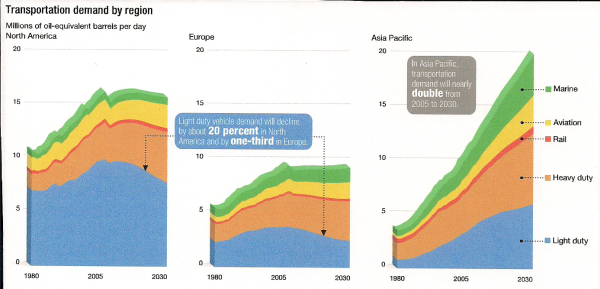

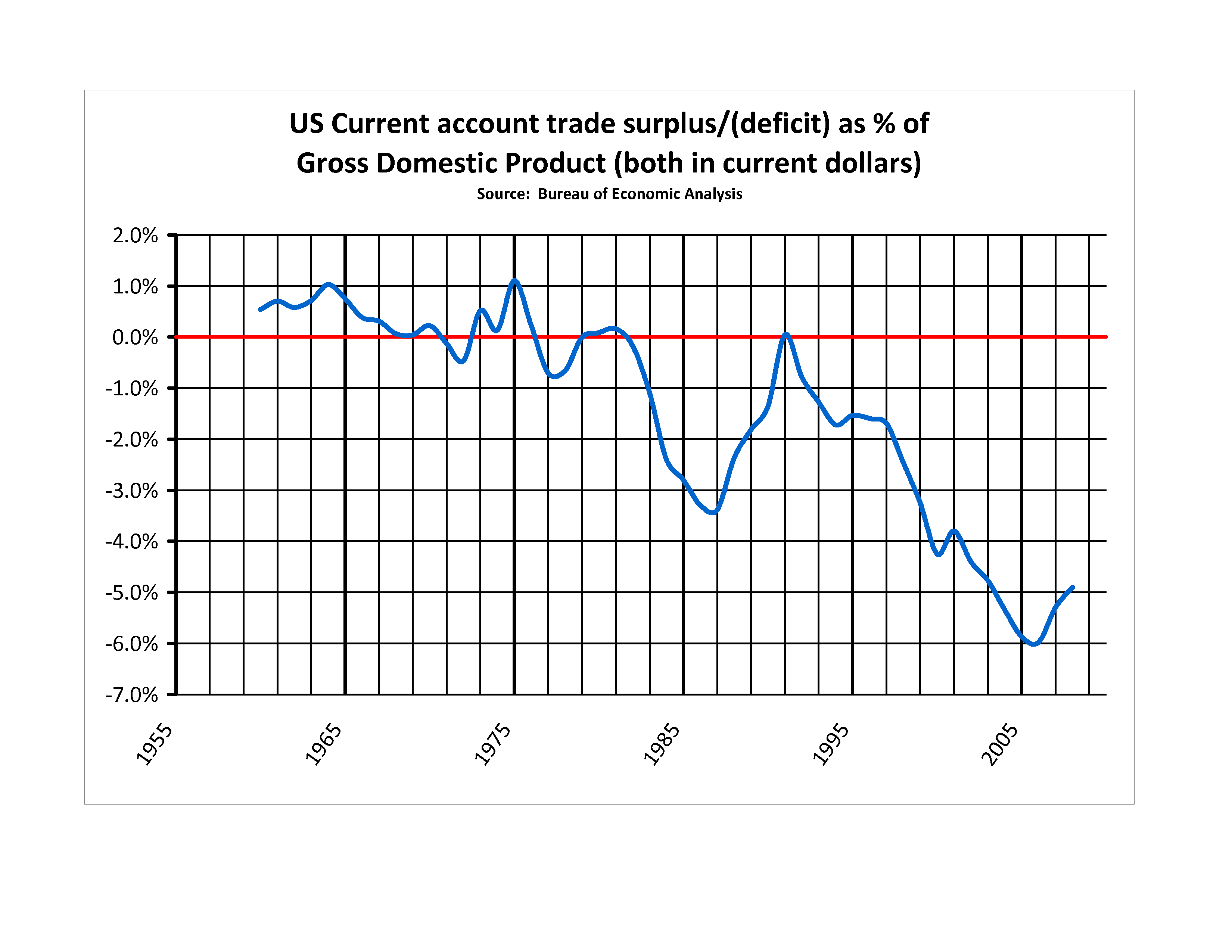

Today, the global economy is characterized by huge trade imbalances. Everyone has focused on exchange rates. That is the wrong focus. China’s net business fixed investment now may be equal to two times the combined fixed investment of Europe, Japan, and the United States. That capacity has to go somewhere. Some of it has to go abroad. Some of it has to substitute imports China now buys elsewhere. This will cause even greater trade imbalances, which will be problematic given the political constraints on using fiscal policy to offset the likely deterioration in America’s external sector (and corresponding increased threats to employment).

We’re now seeing the consequences of our “malign neglect” of China’s economic policies: The Chinese are preparing to dominate the higher tech and capital goods areas — from new Stealth fighters, to high speed railways, to solar, to nuclear. So what happens to the US industrial base when Boeing can’t sell abroad because China has the same line of planes and they are cheaper? Oops! There go our military aircraft exports.

This points to the issue of import substitution, which everyone forgets. Exporting into a country with two billion people is a chimera because China doesn’t really want American exports; they want total self-sufficiency. Building your plants in the land of the two billion armpits is a chimera as well, because the locals will steal your know-how and then undercut you and carve up the domestic market, which they control against you. Look at what is happening to the Spanish wind turbine company, Gamesa, as a recent NYTimes article illustrated:

Gamesa has learned the hard way, as other foreign manufacturers have, that competing for China’s lucrative business means playing by strict house rules that are often stacked in Beijing’s favor.

Nearly all the components that Gamesa assembles into million-dollar turbines here, for example, are made by local suppliers — companies Gamesa trained to meet onerous local content requirements. And these same suppliers undermine Gamesa by selling parts to its Chinese competitors — wind turbine makers that barely existed in 2005, when Gamesa controlled more than a third of the Chinese market.

But in the five years since, the upstarts have grabbed more than 85 percent of the wind turbine market, aided by low-interest loans and cheap land from the government, as well as preferential contracts from the state-owned power companies that are the main buyers of the equipment. Gamesa’s market share now is only 3 percent.

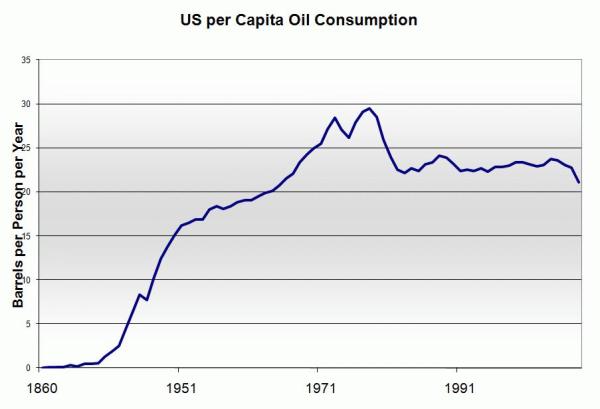

China’s capital expenditure as a percentage of GDP has now reached a historically unprecedented 50% of GDP. Throughout economic history, countries with especially high investment to GDP ratios have embarked on inefficient investments. In the 1820s they built too many canals. In the railroad boom in the UK in the 1840s they built three lines between Leeds and Liverpool but the traffic could barely support one. Throughout the 19th century railroad boom after railroad boom led to busts. We saw a repeat of the same across a broad spectrum of industries during the 20th century, right up to the present day. The oil boom of the 1970s led to gluts of rigs and tankers that were idled for a decade. The bubble decade in Japan produced unneeded private investment that, in the two decades since, has been scrapped and replaced. In emerging Asia in the late 1980s and 1990s excesses of residential investment led to gluts that took a decade to work off. In the past decade the US did in residential construction what emerging Asian countries did a decade earlier.